The director yelled, “cut”, the cameras stopped and the crew was packing up for the day. But the action continued in the shantytown close to the airport in Maputo, Mozambique, where the new biopic “Ali” was filming earlier this year. Despite the lull, Will Smith kept on playing Muhammad Ali, shadowboxing, grooving along the dusty road surrounded by hundreds of adoring kid extras. Suddenly, Smith’s feet left the ground and he was floating on a sea of hands. “Everyone starts shouting ‘Ali, Ali, Ali,’” recalls director Michael Mann. “So, of course, I unwrapped. We started shooting like crazy. Will and Ali had become the same.” When it was over, Smith was teary-eyed.

“I’ve been struggling to intellectualize the emotion,” Smith told TIME a few days later. “There’s no feeling like being black and successful and taking a trip through Africa. And it was the younger kids who knew who I was. But it felt like the people weren’t carrying me through the streets because I was famous. They connected with some aspect of who I am, what I want to be and what I stand for.”

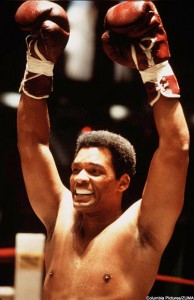

Smith may not be as big as Ali but, sitting in his trailer, wearing a white singlet and olive trousers tied loosely at his waist, the usually  slim and lanky actor looks imposing. His shoulders are huge and his biceps flex whenever he moves his arms. “I’m sharp,” he says, boxing the air in front of him. Smith began training for the role in February 2000 when he first met Darrell Foster, a former middleweight boxer and longtime trainer of former champion Sugar Ray Leonard. “He was out of shape,” says Foster. Foster put Smith through a professional training camp: a three mile run every morning, boxing practice for a couple of hours, a high protein low carbohydrate lunch, then watching fight films together before going off to the weight room. “We went to Miami so he could get used to the humidity in Africa,” says Foster. At first, Smith dropped 10 pounds to around 190, then he started beefing up, peaking at 224 lbs. “He’s great,” says Foster, who helped Mann choreograph the fight scenes. “He could fight for real. His hand speed’s real good.”

slim and lanky actor looks imposing. His shoulders are huge and his biceps flex whenever he moves his arms. “I’m sharp,” he says, boxing the air in front of him. Smith began training for the role in February 2000 when he first met Darrell Foster, a former middleweight boxer and longtime trainer of former champion Sugar Ray Leonard. “He was out of shape,” says Foster. Foster put Smith through a professional training camp: a three mile run every morning, boxing practice for a couple of hours, a high protein low carbohydrate lunch, then watching fight films together before going off to the weight room. “We went to Miami so he could get used to the humidity in Africa,” says Foster. At first, Smith dropped 10 pounds to around 190, then he started beefing up, peaking at 224 lbs. “He’s great,” says Foster, who helped Mann choreograph the fight scenes. “He could fight for real. His hand speed’s real good.”

In the ring in Maputo, Smith floats like Ali. He backs into the ropes, practicing his now famous rope-a-dope. Punches slam into his thick torso and off his protector-covered head. “He’s made himself into a boxer,” says Mann. “We box. We don’t do stuntmen. We don’t do false punches.

He knows it’s coming but he takes the hit. We have footage of him getting knocked down and his head goes ‘wham’ and he goes flying. Man, the spray…” Of course, it’s all choreographed. “I view the boxing as a story,” says Mann. “How do you translate that story into dance using boxing?” Still, all the fighters in the film, except for Smith, were professional boxers.

“He’s become Ali,” the director continues. “And it’s not just the boxing.” Mann remembers when Smith and Ali first met during the shooting. “It was the first time Ali was on the set and the first time Will was boxing with Ali there. And we’re on the speed bag. And Will’s in the ring and he had this look in his eye and I thought, ‘Man, is he going to do this?’ And he launched into the Muhammad Ali voice. The very first time to put on that Muhammad Ali attitude in front of Ali. Ali just looked at him and said to Howard Bingham (the sports photographer and a longtime Ali friend), ‘Was I that crazy? Why didn’t you tell me I was that crazy?”